CRISIS: POLITICS, PRECARIOUSNESS, AND POTENTIALITIES

Crisis seemingly weaves our world together with alarming reports on global pandemics, climate change, financial collapse, poverty, people’s movement and displacement, armed conflicts, and more. Claims to crisis may involve tangible displays but even be exaggerated by populist ideology and rhetoric for political purposes. These might serve to justify rapid shifts in the socio-political and economic landscapes at the national and international level, laying bare power, and other dynamics underlying the responses to these phenomena.

Yet, crisis also refers to sudden incidents and shifts that disrupt the foundation and normalcy of lifeworlds, livelihoods, and communities and thereby make outcomes unpredictable. The social asymmetries inherent to a crisis due to life defining conditions such as gender, age, sexuality, ethnicity, class, and bodyableness, however, are only rarely recognized in the analysis of a given crisis, how it is interpreted, its many-layered impacts, and the policies and strategies implemented to cope with a crisis and its aftermath.

Common approaches to crisis have not kept pace with the increasing complexity in the socio-economic and political systems dealing with a crisis and how a crisis kaleidoscopically is taking new shapes when bouncing between the global and local levels, interlocking with and accelerating already existing crises. The dimensions, phases, and temporalities of a crisis are critical to identify to unfold the differences between crisis as emergency, crisis as a path to renewal, and crisis as a more chronic state of precariousness and difficulties.

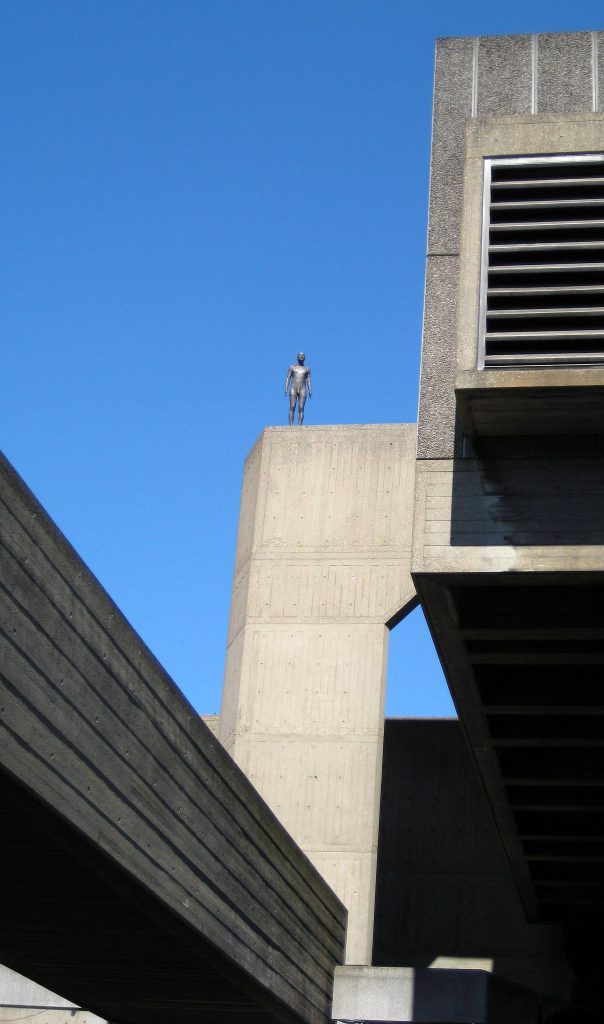

Art: Antony Gormley’s Event Horizon in London, 2007.